In early October I went to the Belkin Art Gallery to see the exhibition Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools. This powerful exhibition, which runs until December 1st, presents artists who have produced work arising from the history of Indian Residential Schools in Canada.

I met with UBC graduate and co-curator Tarah Hogue, and artist Beau Dick to talk to them about the exhibition.

-Tarah Hogue

For those who haven’t seen or heard about this exhibition yet, what would you say is the overall themes of the exhibition, and what kind of art could people expect to find here?

We didn’t want to give an overarching narrative to the exhibition, but rather to present a multiplicity of perspectives on the history and legacy of residential schools, their lasting effects, as well giving some hopeful messages to come out of this history. Our main goal in this exhibition was to educate, because we are located on the unseated territory of Musqueam nation, as well as being on a university campus that has students coming from around the world to study here, students who don’t necessarily know Canadian history let alone the history of residential schools in Canada. We’ve tried to work with artists from a wide variety of backgrounds including artists from across Canada as well as cross-generational. We have senior artists such as Norval Morrisseau, and Joane Cardinal-Schubert, as well as younger upcoming artists such as Chris Bose, Lisa Jackson, and Tania Willard.

Looking on your blog I noticed you are working on two exhibitions relating to Aboriginal issues and residential schools. Are you particularly drawn to art that deals with Indigenous issues in Canada, and what specifically drew you about this exhibit at the Belkin?

Well my background is mixed Dutch and Métis ancestry, and I recently graduated from the Curatorial studies program here at UBC and my focus in part was on contemporary First Nations art. I was fortunate enough to work at the Belkin in a work-study position during my studies, and when it was decided that this project would be happening here I was asked to come on board for the project. It’s been a really formative experience for me, being one of my first experiences in a curatorial setting, and working with a large number of artists many of whom I’ve had the pleasure of getting to know over my time here. It is the type of work I hope to be continuing in the future.

Do you think your studies at UBC have influenced your areas of interest?

I felt a lot of responsibility since starting my program here to engage with First Nations art and artists on a very respectful and responsible level partly because I was funded in my first year by an Aboriginal fellowship and applied specifically to focus on First Nations art. Working through the Art History department was really foundational for me because it introduced me to the cultural and artistic practice of people from the coast. Plus working at the Belkin really allowed me to connect with people, work on exhibitions that asked questions about important social issues, and see how people engage with the art. It was really good experience, I really enjoyed my time in school here.

What type of reaction have you been getting from people?

We have people come through the exhibition that have such a range of responses to it. I’ve talked to students who’ve gone through the exhibition and said that it made them feel ignorant and it made them feel them uncomfortable and I’ve also spoken to people who’ve worked on First Nations issues, are First Nations themselves or who have worked with residential school survivors who’ve said the exhibition has made them feel differently about this history. A history that can be really numbing in terms of the statistics, numbers, and consistency of stories of abuse that you hear. So in that way I think each different experience – the variety of reactions that people have when they come to the exhibition – is really important.

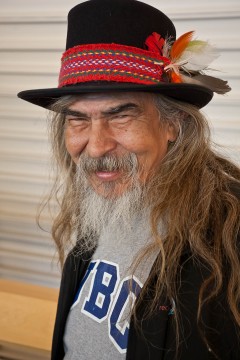

Beau Dick is a Kwakwaka’wakw artist from the community of Alert Bay, on the northern coast of Vancouver Island. Considered one of the finest traditional Northwest Coast artists around today, his work has been shown in museums and galleries around the world. His piece at the Belkin, Ghost Con-fined to the Chair, is based on a vision he had involving an old chair found in a carving workshop at the Alert Bay residential school.

Your piece, Ghost Con-fined to the Chair, is a very powerful one. It really brings out a lot of the old histories from that time.

Yes the history of that chair is so profound, as a survivor to it, ends up being pretty useless as a chair but a great conversation piece, which it was intended to be. Regarldess of what anybody’s views are it evokes some kind of feeling that has to be addressed. This whole exhibiton is totally mind-blowing. Each piece has some impact, some quality. And it’s not always comfortable. It touches a lot of nerves, but I say that is a good thing. Bring stuff to the surface so we can talk about it and sort it out. I think that’s the intent of this show – to open the wound so we can let some of the poison out, heal and move on. Not to forget, but to understand.

You grew up in Alert Bay on Vancouver Island. How did you become interested in carving? Who taught you?

My father and my grandfather were my main sources of teaching and inspiration when I began. I did go to UBC and took courses over a few summers with Doug Cranmer (famous Kwakwaka’wakw sculptor) who was my grandmaster and I have felt extremely honoured to have followed in his footsteps, doing similar work to Doug in preservation and restoration and teaching of these traditions.

Were there lots of people carving when you were growing up?

Not among the Kwakwaka’wakw. When I was coming up there weren’t many people interested in acquiring the skills of the traditional carvers. But eventually that changed, around the 1980’s there was a surge of young people starting to become interested to the point where today there are many gifted younger artists.

Partly due to artists like you, Doug Cranmer, Bill Reid, and others.

Yes I think we did all play a part and contributed to this rise. I have teenagers and people in their early 20s working with me today. It helps me stay connected and up to date too.

You’ve spoken of your art as keeping past traditions alive. I was wondering how you balance the idea of your traditional work with the fact that you are a modern artist showing your art in galleries and museums around the world.

Well in this day and age what it is is that I need to go to the marketplace so I can afford to continue working on the traditional side, so they are sort of connected in some way. I can go sell a mask, which affords me the time to carve one for the family or another family in the community, or work on a totem to put up in my village. That’s something I can really take pride in. Become a world-renowned artist you know, so what? I mean that’s cool but that’s not the meat. The meat is at home, and I’m really proud of what I’ve done in terms of restoration and preservation and keeping the fire lit.

You’re also quite politically active. In February you led a march from Alert Bay to Victoria, a 500 kilometre walk in protest of the destructive impacts of fish farms on the region. Do you see a connection between your art and activism?

I don’t really look at it that way. I think gaining some sort of popular status gives me an opportunity to speak about these issues. It happened quite naturally. Responsibility falls on your lap and you have to make choices. If you want to take action and have conscientiousness that’s your choice. I was fortunate to have my daughters, who are brilliant, as the driving forces behind that event. They made that event possible. I was a figure as the head of the family but I really give them the credit for doing all the organizing.

I do think though that these issues are really pertinent to our survival. The issues we have as First Nations, our concerns, are really everybody’s concerns. There’s a lot at stake here, our whole credibility as Canadians is at stake. Where do we stand now and where do we go from here is the question. Are we ready to reconcile and face the truth? As the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and further discussion continues to challenge us. There’s a lot happening right now, and there’s a lot of focus on our culture. For a while Northwest art was a fad, when things were flying off the walls of galleries all over town, but that’s lulled. People are looking for the real thing now.

The TRC events and the Idle No More movement have helped inform the general public about some of the issues facing our country and it’s relationship with Indigenous peoples, but there is still a long way to go. What do you see as some of the biggest hopes, and biggest challenges facing future generations of Canadians?

The only advice I can give to young people is to try and be better than us. Aspire to do a better job than we did, and things will improve. Here we are together; there has to be harmony if we’re going to survive. We are the ones responsible. We’re all in the same canoe. Hopefully we’re paddling in the same direction or else we’re not going to get anywhere! I’ll leave it at that.

“Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools” runs until December 1st at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery. Entrance is free for all UBC students. The Gallery is hosting a symposium on Friday November 15th from 9am-5pm in the Lillooet Room in Irving K. Barber Learning Centre. There will be many lectures scheduled throughout the day. You can find out more here:

-Sam

Photo credit – Beau Dick, 2013. Photo: Michael R. Barrick, UBC Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery